I have retired the show with this week’s farewell program. I’m healthy . . .just hewing to my philosophy of ending activities when they are still fun to do. I’ll explain this a bit more but first go ahead and demonstrate your multitask abilities by starting the show while still reading. (I have returned to the air with a Thursday drive time show from 4 to 6 p.m. PST in which I focus on up tempo tunes, liberally lacedwith New Orleans music. But I don’t record the show, you have to catch it live. )

Since September 8 2014 (until mid-March 2022), I produced a weekly radio show that features “Just a Little Bit of Everything ” which is the title of the Herb Hardesty’s 1961 single that kicks off the first full set of music. However, the common element has always been a strong connection with New Orleans and Lafayette.

The show broadcast live from the KAOS studio on the campus of The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, first on Mondays and then later on Thursdays. A few years back, community station KMRE (Bellingham) began running edited versions of the show on Fridays. More recently, the show has aired on KOCF (Fern Ridge), WPHW (Hartwell) and occasionally other stations that participate in the Pacifica Network. In all, I produced about 380 episode with over 300 of them available to listen through this website.

When I first started as a volunteer deejay with KAOS , I considered a show featuring exclusively New Orleans music. But worried about the limited format. Over the course of my first year doing a morning drive-time show, I found myself digging into the KAOS music collection and was surprised by the depth of music coming out of the city –my birthplace and home for most of childhood.

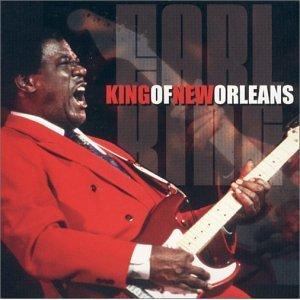

So that’s what I’ve done, play songs by musicians such as Earl King who kicks off the show with “No City Like New Orleans,” Johnny Adams who swings through “Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You,” and Aurora Nealand and the Royal Roses jamming through “Minor Drag.”

I’m not a fan of long goodbyes but I also believe its important that radio stations provide closure when a show ends (as opposed to abruptly changing format with no warning). So I made it a finale show and asked listeners to call in and say hi. And over a dozen did! My favorite comment was from a listener who said she was going to JazzFest this April as a result of what she had heard on the show. (I couldn’t have received a better report card.)

Today’s show takes a sentimental walk through some previously covered material, including “St. James Infirmary” a personal lifelong favorite which has an interesting pedigree. Here’s more detail on that history. This week’s segment includes a clip from the Treme TV series featuring Wendell Pierce riffing off that song in the Touro Emergency Room.

Later, I play the original version of “Basin Street Blues” by Louis Armstrong and hint at its fascinating history detailed more in a previous show and post including how that song acquired lyrics which then resulted in the City of New Orleans returning the “Basin Street” name after eliminating it during a blush of civic post-Storyville shame (I guess tourism promotion beat out virtue and vanity). Satchmo scats on this early pre-lyric version of the song.

The Treme Brass Band does a great job on “Darktown Strutters Ball” a song with lyrics and a title that has caused me concern and in which I explore in a show and post.

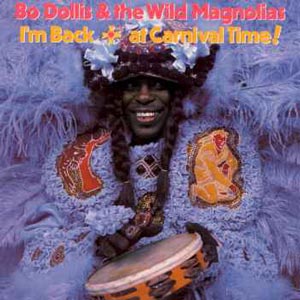

I touch on the topic of Nine Lives a book by Dan Baum about people’s lives in New Orleans — originally sent to write about Hurricane Katrina, Baum ended up with a book detailing unique aspects of New Orleans culture such as Mardi Gras Indians, and marching bands. I play a song about Tootie Montana in today’s show.

This week’s show also includes a couple of clips from interviews including a funny description by Irvin Mayfield of his good friend Kermit Ruffins. You’ll also hear Kermit sing from his Happy Talk release. Here’s the interview of Kermit and Irvin in Kermit’s Mother-in-Law club about their album collaboration.

You’ll also hear Craig Klein saying why his New Orleans Nightcrawlers, which won a Grammy last year, sound so authentic. I pull that clip from an interview with four-ninths of the band last year.

And you’ll hear an example of the messages I aired from New Orleans musicians during the COVID quarantine of 2020. For my final show, I chose Marla Dixon to repeat her delightful summary of her COVID life. Here’s the full show and full recording of Marla’s message from that time.

So this is it. I’m done creating new shows though you can listen to the 300 shows available through this website. I’m looking to travel a bit more and explore even more new music. And I’m going to keep this blog going. I suspect it will be quiet for a few weeks but don’t be surprised if I return with non-radio show type posts regarding music. Thanks for listening. But to keep in touch, you should subscribe .(right hand column)

In honor of the Soul Rebels’ tuba player, Damion Francois’s 46th birthday, I start the show with the band knocking out “Let Your Mind Be Free.” The Young Tuxedo Brass Band keeps the second line moving with Little Freddie King and the Red Hot Brass Band helping out with their own songs.

In honor of the Soul Rebels’ tuba player, Damion Francois’s 46th birthday, I start the show with the band knocking out “Let Your Mind Be Free.” The Young Tuxedo Brass Band keeps the second line moving with Little Freddie King and the Red Hot Brass Band helping out with their own songs. The show kicks off with Theryl “Houseman” Declouet with his infamous introduction regarding the third world status of New Orleans at a Galactic concert and flows quickly into Shamarr Allen’s “Party All Night.” Al Hirt takes a turn and so does patron saint of this website and the show,

The show kicks off with Theryl “Houseman” Declouet with his infamous introduction regarding the third world status of New Orleans at a Galactic concert and flows quickly into Shamarr Allen’s “Party All Night.” Al Hirt takes a turn and so does patron saint of this website and the show,  As the bandleader and composer for The Roamin’ Jasmine, Smith has become well acquainted, as do most successful New Orleans musicians, with the city’s traditional jazz standards. But its been his ability to apply a New Orleans style rhythm and blues spin on classic blues numbers that sets his music apart.

As the bandleader and composer for The Roamin’ Jasmine, Smith has become well acquainted, as do most successful New Orleans musicians, with the city’s traditional jazz standards. But its been his ability to apply a New Orleans style rhythm and blues spin on classic blues numbers that sets his music apart.