With the onset of African American History Month, I thought it worthwhile to address the role of New Orleans in launching Rock n’ Roll. Cause the very fact that the city’s contribution is relatively unknown is a reflection in part of the broader subjugation of the African-American credit for creating the music in the first place.

Whether you date the beginning of Rock n’ Roll to Louis Jordan’s Saturday Night Fish Fry, Roy Brown’s Good Rockin’ Tonight, Fats Domino’s The Fat Man, or even the non-New Orleans recording of Rocket 88 by Jackie Brenston, what’s abundantly clear is that this music originated from African Americans–not white boys like Elvis Presley and Bill Haley.

Alan Freed, the white deejay credited for popularizing the term Rock n’ Roll, essentially used the term to rebrand Rhythm and Blues which was associated with black music. For that matter, the term Rhythm and Blues was created by a Billboard Magazine writer in 1949 to replace the previously used term “Race Music.”

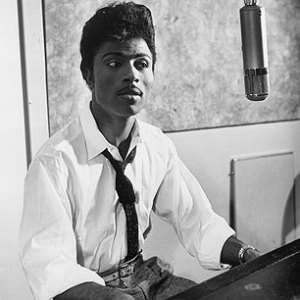

Back to New Orleans, many of these early Rock hits were recorded in the J&M Studio on Rampart Street on New Orleans — located within a Russell Wilson touchdown pass of Congo Square where people of color (free and enslaved) gathered on Sundays and practiced the drum beats and rhythms that fueled jazz, swing, jump blues and Rock n’ Roll. The studio also recorded a great many other early Rock hits, including almost all of Little Richard’s hits.

Through radio, white youth were exposed to black artists–a wonderful testament of the integrating power of the air waves. In a bizarre twist, some white deejays hosted “Rhythm and Blues” shows and pretended to be black when introducing the songs. To sound authentic, a New Orleans deejay hired an African American to write his script.

While Fats Domino is unlikely to be included in the pantheon of civil rights leaders, his music and performances went a long way toward breaking down the walls of segregation. First, his records sold more than any artists other than Elvis during the 50s. (One million copies of The Fat Man were sold within the first three years of its release)

But it was in Domino’s performances where push came to shove. After all, can you really stand still to his music? (Go ahead, try!) Even though performance halls attempted to segregate white and black audiences, dancing ensued and elbows rubbed, flummoxing police and other security who often caused riots by trying to break up the mingling.

That mingling particularly scared Southern segregationist who contributed to the public venom poured on Rock n’ Roll, providing more than the usual incentive for music promoters to put a white face on this popular music.

Yet Domino continued to perform throughout the country, at a time when black musicians often had to sleep in their cars or buses because hotels would not accept them.

When he appeared on television, his band, all African American musicians, were often hidden from sight.

If you’re interested in learning more about Fats Domino during his period, I recommend “Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock n’ Roll” by Rick Coleman. It was Coleman’s book who tipped me off to the Pat Boone shadow. Boone recorded a number of African American rock numbers, illustrating just how easy it is to sap the soul from a number.

Here is Fat’s doing Ain’t That a Shame. And here’s Boone doing the same song which he apparently wanted to retitle “Isn’t That a Shame”. . . It sure was.