I use this blog as way to prepare for my radio show on the Olympia community radio station, KAOS. Here’s some of the things I learned this year.

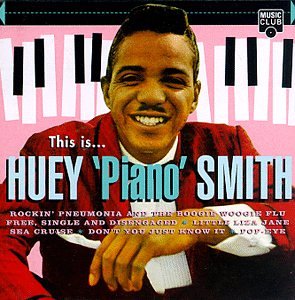

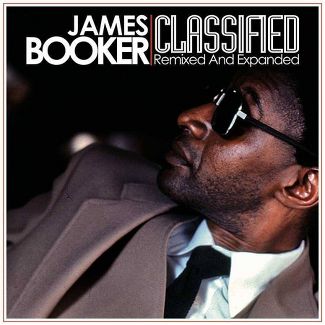

Fascinated by the role of the piano in New Orleans, I started a series on New Orleans piano players that now includes James Booker, Allen Toussaint, Professor Longhair, Tuts Washington, and Dr. John. (More to follow).

During the carnival season, I explored the traditions and music of Black Indians of Mardi Gras . That story led me to write about the importance of African American musicans from New Orleans in creating rock n’ roll. I followed that up with Fats Domino and the role his performances played in getting black and white audiences to dance to the same beat.

Speaking of Mardi Gras, I provided a personal reminiscence then added a new Mardi Gras experience of bar hopping with the local brass band, Artesian Rumble Arkestra.

My entry on New Orleans women in music resulted in one of my favorite radio shows of the year and helped me grow my knowledge of New Orleans music and the many wonderful women who create it.

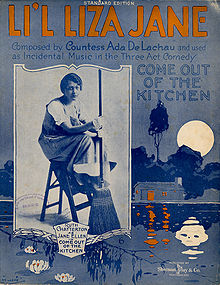

I chose my Valentines show to dive into the history of the often recorded “Careless Love.” Later I looked into the history of another New Orleans standard, L’il Liza Jane. I also tracked down songs about “sugar” which, as you’ll find, really are not about sweet granules. I also explored the Afro-Cuban connection or what Jelly Roll Morton called the “Spanish Tinge.” (Last year, I wrote an entry on the classic and checkered history of St. James Infirmary.)

One of my more popular entries was about the Galactic tour of 2015 when it played Bellingham, Seattle and Portland. Interestingly, the funk band is playing Seattle and Portland about the same time in February of 2016.

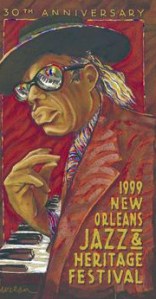

As you might expect, I have several entries on New Orleans institutions, including the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Preservation Hall, the jazz funeral, the Freret Street Festival, French Quarter Festival, and the end of smoking in New Orleans nightclubs.

As you might expect, I have several entries on New Orleans institutions, including the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Preservation Hall, the jazz funeral, the Freret Street Festival, French Quarter Festival, and the end of smoking in New Orleans nightclubs.

Drawing on my April trip to New Orleans, I wrote about the magnetic pull of New Orleans to young musicians of all genres. I also shared my experience of touring the currently closed Dew Drop Inn with the grandson of its founder.

The 10-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina inspired a couple of entries, including this one that chronicled the activities of some of New Orleans better known musicians. This entry also has links to my two radio shows honoring that anniversary with music and excerpts from Spike Lee’s documentary.

And I finished off the year, as I did last year, with a short catalog of the 2015 New Orleans music releases featured on my show. Part 1. Part 2.

I hope you enjoyed the music and the little bit of information I learn and share. I know I do. Subscribe if you’d like to follow what I learn in 2016. Happy New Year.

“The studio was like a Mardi Gras reunion, everybody laughing and talking, telling stories all at the same time. But once we got settled, the vibe was there and the music just flowed.”

“The studio was like a Mardi Gras reunion, everybody laughing and talking, telling stories all at the same time. But once we got settled, the vibe was there and the music just flowed.”

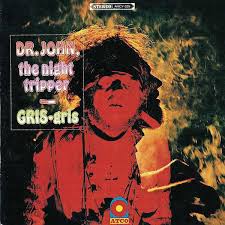

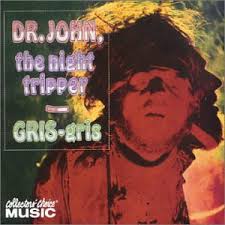

Not surprisingly, songs about gumbo are my favorite. Gris Gris Gumbo YaYa, the first cut off of Dr. John’s debut album, was partly the inspiration for the

Not surprisingly, songs about gumbo are my favorite. Gris Gris Gumbo YaYa, the first cut off of Dr. John’s debut album, was partly the inspiration for the