If there is justice in the music world, James Booker would be better known for the genius and artistry of his piano playing. The fact that his music is still played 30 years after his untimely death in New Orleans offers some hope that justice may ultimately be served.

Classically trained but also taught by Tuts Washington and influenced by Professor Longhair, Booker came of age in the heyday of New Orleans R&B era when Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew and Huey Smith were rocking the jukebox with singles recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s studio.

Booker got in on the act as a studio musician as well as fronting his own songs with “Doin’ the Hambone” and “Thinkin’ About my Baby.” His song “Gonzo” charted nationally and his playing style, sometimes described as a nest of spiders on the keyboards, was admired by many, including music lovers in Europe where he spent some time and built a following.

But while Booker was a versatile musician, capable of playing a wide range of styles, including working with Freddie King, Aretha Franklin, Ringo Starr, the Doobie Brothers, Maria Muldaur, and Jerry Garcia, his star never quite rose to the level of his talent and genius. (Check out this sound recording of a rehearsal session with Booker and Garcia.)

It’s a sad but familiar story; he had his issues. Some, in retrospect, have pondered whether he suffered from a mental malady that in our current day might have been more successfully treated by means other than with heroin and alcohol.

He died way too young in the emergency room of Charity Hospital in 1983 at the age of 43.

Booker was able to bring elements of many musical genres together and his interpretations of familiar songs are unique and probably difficult to duplicate given his skill.

Booker’s “absolutely unique style is a polyglot mix of gospel, boogie-woogie, blues, R&B and jazz, all executed with a thrilling virtuosity,” wrote Tom McDermott who is himself an amazing pianist from New Orleans.

When I listen to Booker’s music, I hear shades of the “Spanish Tinge” made famous by Jelly Roll Morton. His hyperactive right hand razmatazz and left hand syncopation are reminiscent of Professor Longhair. And yet, his style builds on those masters rather than replicates. And he passed the tradition on by tutoring Dr. John and Harry Connick Jr.

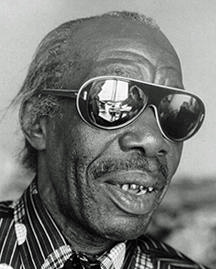

As always, its best if you hear for yourself. I’ll be playing from a few of his solo recordings on Monday but if you have time, consider checking out his last recorded performance at the Maple Leaf. He had a regular gig at the Uptown New Orleans bar, often playing to sparse and disinterested audiences. The Booker you see in this video contrasts sharply with the more flamboyant Booker of earlier years. His teeth are fixed, he’s wearing a suit and not wearing his trademark patch with a star on it over his left eye. Here’s a video of that period in his life.

Helping to bring the world’s eye to Booker’s talent is a documentary called the Bayou Marahaja by New Orleans filmmaker Lily Keber.

“Bayou Maharajah explores the life and music of New Orleans piano legend James Booker, the man Dr. John described as “the best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced.” A brilliant pianist, his eccentricities and showmanship belied a life of struggle, prejudice, and isolation. Illustrated with never-before-seen concert footage, rare personal photos and exclusive interviews, the film paints a portrait of this overlooked genius.”

I have none seen this film; no distributor yet. I’m hoping it can be shown at the Olympia Film Society’s Capitol Theater. But you can check out the trailer and join me in honoring and enjoying his talent. I’ll be spinning some Booker tunes along with my usual mix of New Orleans music this Monday on Sweeney’s Gumbo YaYa.