It’s not every retirement that results in a musical revitalization. But that’s what happened when veteran jazz performers Danny and Blue Lu Barker returned to New Orleans in 1965.

I suspect they sought a slower pace after 35 years of performing with Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday and a long list of other jazz notables. But retirement for Danny Barker didn’t mean doing nothing.

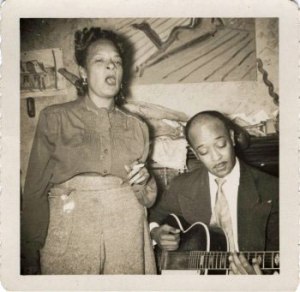

Danny went to work as an assistant curator for the New Orleans Jazz Museum– gone now but the collection resides in the Old U.S. Mint building. He also continued his reputation for performing and writing bawdy songs like the one that made him and Blue Lu famous, Don’t You Feel My Leg.

Danny continued to perform with his guitar and banjo regularly around town, even maintaining a weekly spot with the band at the Palm Court Jazz Café until near his death in 1994. (The gig inspired his song Palm Court Strut. See it performed at Seattle’s Fremont Solstice Parade.)

But it was volunteer work organizing a youth band for his 7th Ward neighborhood church at the request of his pastor that would leave a lasting impact on New Orleans music.

When Barker began recruiting young musicians for the Fairview Baptist Church Christian Marching Band in 1970, brass bands were the province of old men. There was some concern whether the tradition would get carried forward. Fortunately, there were plenty of young musicians developing through the public school’s music system. All they needed was some guidance.

Leroy Jones, who lived only an Archie Manning pass away from the church, was one of the first to get recruited. Danny found the future member of the New Orleans Jazz Hall of Fame practicing in his parent’s garage. Years later, Jones described his initial impressions of Barker this way to Offbeat Magazine:

“We didn’t really know who Danny was in terms of his status. I just thought he was a cool guy. He wore a nice hat and these slick, creased pants and Stacy Adams shoes. He had a cool, hip walk. He was the epitome of coolness. These guys today have nothing on Danny Barker.” (Hear Leroy Jones describe his meeting with Barker on this WWOZ podcast.)

The list of band members that Barker assembled makes it clear he had eye for talent because it reads like a “whose who” of New Orleans musicians: Wynton Marsalis, Gregg Stafford, Herlin Riley, Michael White, Lucien Barbarin, Kirk Joseph, Alton “Big Al” Carson, and Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen, among others.

The Fairview Band played for about four years before Barker had to quit the project because of concerns raised by the local music union. But the band continued, evolving into the Hurricane Brass Band and then Tornado Brass Band–names suggestive of the power produced by these young lungs.

Three of the band members, Gregory Davis, Kirk Joseph, and Kevin Harris, would form the the Dirty Dozen Brass Band which captured the attention of music lovers all over the world by blending traditional brass sounds with funk, bepop and R&B. The band was a major inspiration for the founding members of the Rebirth Brass Band and other brass bands that followed. Without Danny Barker’s efforts with Fairview, the brass band scene in New Orleans would not be as robust as it is today.

Also, many of the Fairview band members such as Jones, Stafford and White, would carry on the tradition of New Orleans jazz, helping to sustain and grow the city’s reputation as the birthplace of jazz.

In reading the many articles about the Fairview Brass Band and Barker’s influence (a good example), I’m struck by how a string musician could affect so dramatically brass band music. He did it by teaching these young players the history and tradition of jazz. particularly New Orleans jazz. He demonstrated the importance of showing up on time, dressing appropriately and being prepared to perform–what workforce professionals now call the “soft skills.” In short, he taught kids who had musical talent how to be professional musicians.

You’ll hear some of Danny’s proteges in this week’s edition of Sweeney’s Gumbo YaYa. See you on the radio.

Not surprisingly, songs about gumbo are my favorite. Gris Gris Gumbo YaYa, the first cut off of Dr. John’s debut album, was partly the inspiration for the

Not surprisingly, songs about gumbo are my favorite. Gris Gris Gumbo YaYa, the first cut off of Dr. John’s debut album, was partly the inspiration for the