Perhaps its a stretch to compare the Dew Drop Inn to Congo Square. But I see similarities between the two. (You can listen to the show while reading this post)

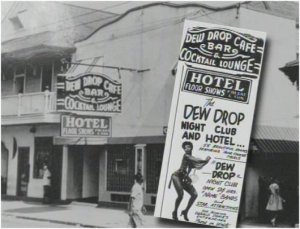

Just as Congo Square served as a gathering place for African American commerce and cultural exchange up through the mid-19th Century, the Dew Drop Inn in New Orleans provided a safe and comfortable place for New Orleans musicians of the mid-20th Century to gather, support each other and play music.

One served as the genesis for Jazz and the other was an incubator for New Orleans R&B and early rock and roll. The Dew Drop Inn was not just a nightclub and bar, it was a vital regional center for African Americans, particularly musicians, at a time when the South and New Orleans enforced apartheid.

I’m not sure if those thoughts initially entered Frank Painia’s head when he decided to expand his barbershop on LaSalle Street to include a restaurant and bar. Most likely, he just saw a business opportunity across the street from where one of the largest housing projects in New Orleans was being built (the Magnolia Projects). By expanding his business, he provided employment for his brothers and eventually other relatives. He christened it the Dew Drop Inn in 1939.

With America mobilizing for the war effort, Painia added a hotel next door so African Americans on the move would have a place to stay when visiting or passing through New Orleans. The combination of barbershop, restaurant, lounge and hotel made the Dew Drop Inn a convenient stop for travelers.

But it was Painia’s venture into booking performers that would put the Dew Drop solidly into music history. He started by producing shows at a nearby boxing arena and high school auditorium. Since he had the Dew Drop, he could house and feed the touring musicians, who in turn would jam in the lounge after the official performance. It wasn’t long though before he started booking local acts to perform at the Dew Drop.

Then in 1945, just in time to entertain returning soldiers and their dates, Painia built the “Groove Room.” Located behind the Dew Drop, this two-story music and dance hall with a balcony and elevated band stage established an upscale ambiance with top-flight performers of the day, including Billie Holiday, Big Joe Turner, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and Amos Milburn. Later Ray Charles, James Brown, Solomon Burke, and Bobby “Blue” Bland would grace the stage. Many homegrown performers including Earl King, Huey “Piano” Smith, and Allen Toussaint launched their careers from the Dew Drop.

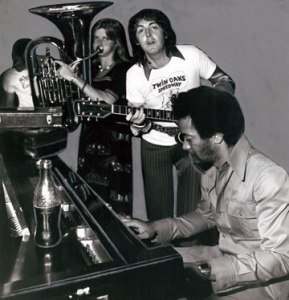

The Dew Drop was home for many musicians, whether passing through or getting their act together. It was a 24-hour operation where musicians could eat, meet, clean up with a haircut, shoeshine and shower, and plan their next step. They would play for white audiences downtown then head back to the Dew Drop and jam with the house band or whoever was performing until daylight.

The nightclub show included an emcee, comedians, magicians, dancers and, of course, the bands. It was not uncommon for the emcee or some of the dancers to be female impersonators (to use the term of that day). Bobby Marchan, who would sing with Huey Smith and the Clowns, got his start in New Orleans as part of a drag show called the Powder Box Revue.

Most New Orleans musicians of that period have stories about the Dew Drop. Grandpa Elliot Small of Playing for Change remembers watching his uncle play the harmonica there. Deacon John tells of how he broke into the recording business when he was approached by Allen Toussaint while playing guitar at the Dew Drop. “My head just popped open at the opportunity . . .the very next day we were in Cosimo’s studio recording with the great Ernie K-Doe. “

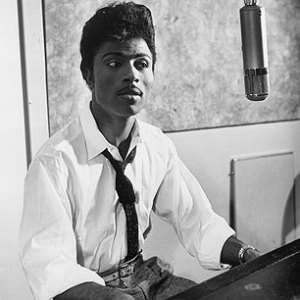

But my favorite story is how Richard Penniman got his mojo at the Dew Drop Inn. Things weren’t popping in J&M studio that September day in 1955. Producer Robert “Bumps” Blackwell, a native of Seattle, called for a break and took his young protege for a drink. It was a slow day at the Dew Drop until Richard discovered the upright piano in the corner and banged out a tune so bawdy that Blackwell had to hire a writer to clean up the lyrics. Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti was a crossover hit that propelled him to national fame.

While the Dew Drop Inn was established, owned and frequented by African Americans, white patrons were allowed in. But this meant that Painia was arrested at times when police raided his business and charged him with “racial mixing.” Eventually, he successfully sued the city, establishing the right for businesses to serve any customer they wanted.

By the end of the 60’s, changing musical trends, desegregation and Painia’s declining health brought an end to Dew Drop Inn’s musical performances. The business carried on mostly as a hotel until Hurricane Katrina caused so much damage, it could not reopen.

The building still stands in its Central City neighborhood but is shuttered. Yet, Painia’s grandson, Kenneth Jackson carries a long-held torch that the Dew Drop will once again serve as a social and music hub for the community.

I’ll have that story in next week’s post (available now). Here’s the podcast of the show featuring musicians who played at the Dew Drop Inn and we’ll hear in Mr. Jackson’s own words about the Dew Drop’s glory days.