Welcome to this site on New Orleans music. There are four posts about New Orleans standards that are attracting more attention now than when originally posted. Since these posts are accompanied by one of my shows, I thought I would make it easier to read and listen to them..

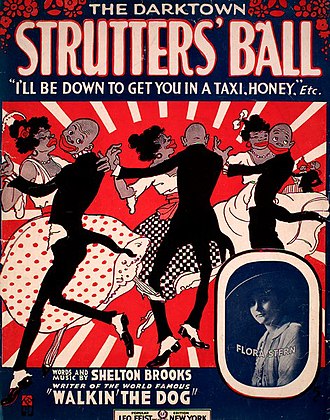

Recently, my number one visited page provides the back story on “Darktown Strutters Ball.” When I prepared for this show a few years back, I was conflicted over the use of a racist term for African-American neighborhoods and yet there was this amazing song that used it. The post and the accompanying show delves into the context of the song written by African-American composer Shelton Brooks and how various artists handle the song. If you listen to the show, you will hear five versions of “Darktown Strutters Ball.”

Next on the resurgent reading list is my post and show about Basin Street Blues. Composed by Spencer Williams who lived in Mahogany Hall on Basin Street and originally recorded by Louis Armstrong, who grew up in that neighborhood at the height of its notoriety, the song has evolved over the years including the addition of an opening musical phrase and lyrics (with a Glen Miller assist). You’ll get the full story and listen to the show here. The street has evolved too.

My post on Lil Liza Jane scores the next top spot in recent views. The post and show explores adaptability of this minstrel era song which has been updated and adapted by a variety of artists, including groups who follow in the tradition of the Black Indians of Mardi Gras. If you read this post (and listen to the show), feel free to leave a comment in a call and response style as one reader did.

Finally, the New Orleans standard (without a New Orleans back story) “St. James Infirmary” continues to get attention from readers and listeners. This was actually the first post and show I did focusing on a particularly standard. And I loved the history of it. Here it is.

A reminder that I’ve retired Gumbo YaYa and replaced it with a non-recorded live drive-time show on Thursdays on my community radio station KAOS. I play uptempo music and often draw from my New Orleans library. You can stream the show live and listen to the most recent shows using Spinitron (just type in the date and time into the ARK player that corresponds with my most recent show time adjusted for your location)

Basin Street Blues is another New Orleans jazz standard with a fascinating back story.

Basin Street Blues is another New Orleans jazz standard with a fascinating back story. Williams version of Basin Street was a 12-bar blues tune without lyrics. In the 1928 and 1932 Armstrong recordings, Satchmo scats the song’s vocal parts. But in 1931, Jack Teagarden sang the song with a group called The Charleton Chasers with lyrics, that according to Teagarden’s recollection, were written by him with help from bandleader Glenn Miller.

Williams version of Basin Street was a 12-bar blues tune without lyrics. In the 1928 and 1932 Armstrong recordings, Satchmo scats the song’s vocal parts. But in 1931, Jack Teagarden sang the song with a group called The Charleton Chasers with lyrics, that according to Teagarden’s recollection, were written by him with help from bandleader Glenn Miller.